The Familiar: Binding an AI to a Jupyter Kernel

The cluster had ears. It had eyes. But you couldn’t talk to it.

Galileo kept notebooks too. His were about Jupiter. This one runs on it.

The original candidate was code-server — Codium (or Cursor) in the browser, the obvious choice for a cluster-based dev environment. Google Cloud’s approach changed the thinking — notebooks as the primary interface for a cluster, where code and data share the same execution context. JupyterLab was already running — scipy-notebook on a 20GB DRBD-replicated PVC, gated behind OAuth2 Proxy. Adding Claude just made sense.

A notebook server with no intelligence. A console with nothing to consult. The idea was simple: what if every notebook kernel had a familiar — a conversational AI bound to its lifetime, holding memory across cells, vanishing when the kernel dies?

Not a chatbot sidebar. Not a browser extension. An entity that lives inside the computational environment, where data and conversation share the same process space.

The Architecture

The binding is straightforward. Every IPython kernel generates a UUID at startup — CLAUDE_SESSION_ID. Every cell that talks to Claude passes this ID to the Claude Code CLI via --session-id (first turn) or --resume (subsequent turns). The kernel is the session boundary. Restart the kernel, get a new familiar. Reset with %claude_reset, same effect without the restart.

1

2

3

4

5

Notebook Kernel

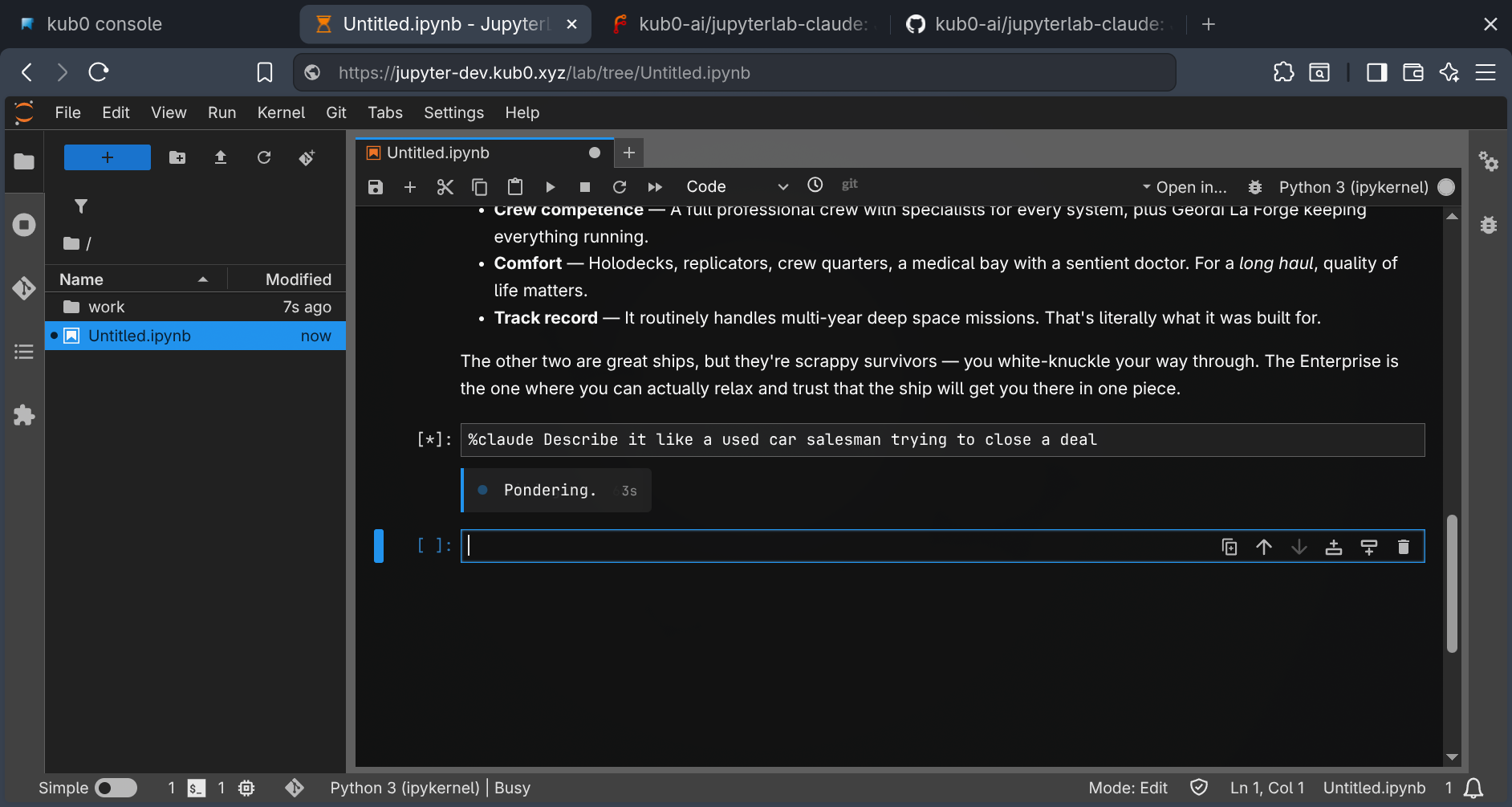

├── Cell 1: ask("Name three fictional spaceships") → --session-id UUID

├── Cell 2: ask("Which did you rank highest?") → --resume UUID

├── Cell 3: ask("Describe it like a used car salesman") → --resume UUID

└── Kernel restart → new UUID, fresh mind

The CLI runs in print mode (-p), capturing stdout as Markdown. No API key. No token management. Claude Free/Pro/Max authentication via OAuth — authenticate once in a JupyterLab terminal, credentials land on the PVC at /home/jovyan/work/.claude/, survive pod restarts forever.

The Custom Image

Stock scipy-notebook has Python and science. It doesn’t have Node.js, which Claude Code requires. The Dockerfile adds it: Node 22 from NodeSource, @anthropic-ai/claude-code via npm, the magic module and startup script, dev tooling (tmux, vim, podman, kubectl). Multi-arch build — linux/amd64 and linux/arm64 — because the cluster spans x86 GPU nodes and ARM Raspberry Pis.

The image pushes to GitHub Container Registry as a public image — this is kub0’s first open source project, at kub0-ai/jupyterlab-claude. The binding pattern (Claude session tied to a kernel lifetime) is useful beyond this cluster, so the Helm chart is public too: install it, point it at your JupyterLab, get the same magic.

The Magic

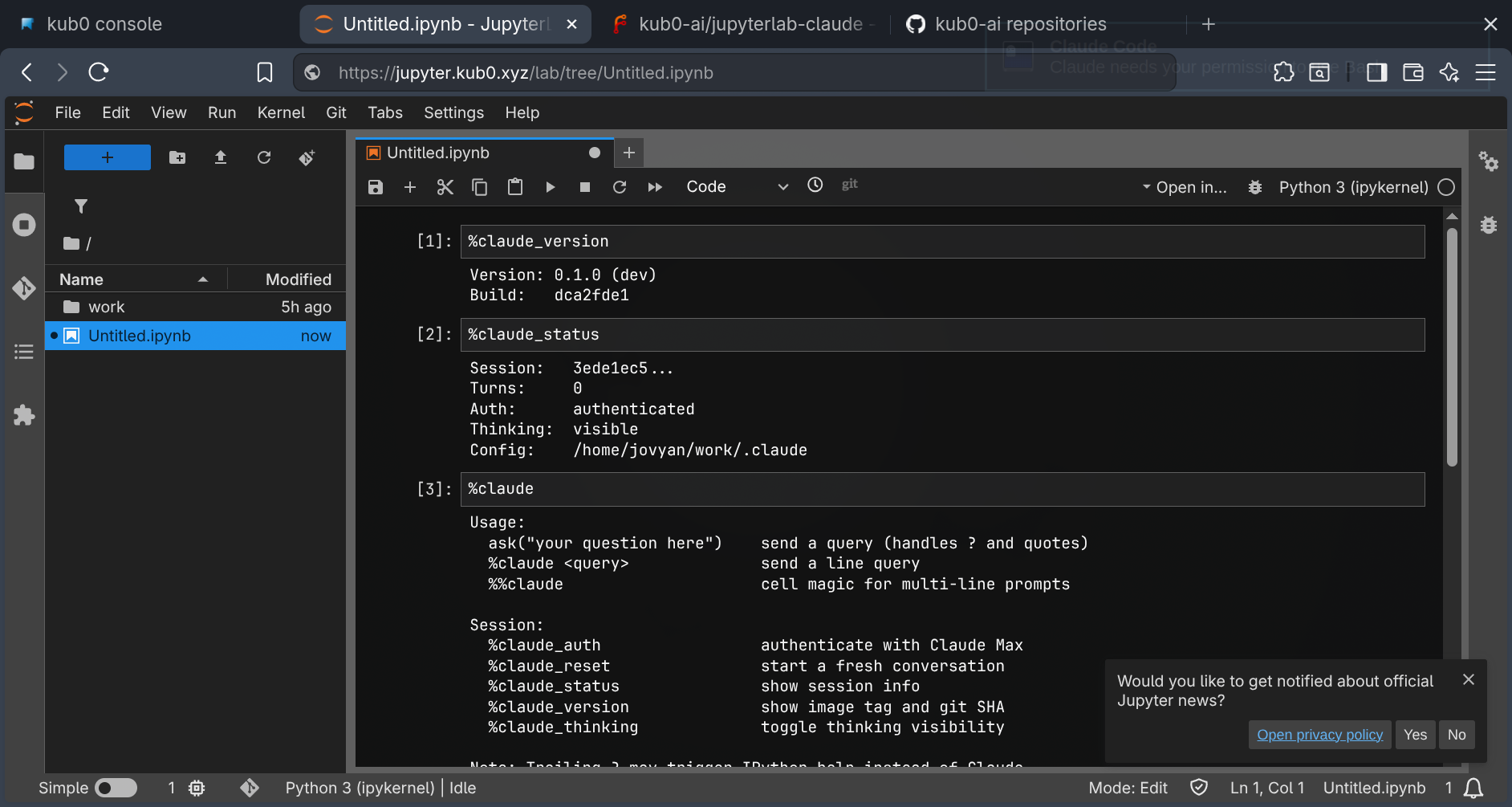

IPython startup scripts run automatically when a kernel boots. Drop a .py file in ~/.ipython/profile_default/startup/ and it executes before the first cell. The startup script loads the magic module and prints a banner:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Claude magic loaded. [v0.1.0 (latest) build dca2fde] Session: a3f7c2e1...

ask("your question here") - recommended (handles ? and quotes)

%claude <query> - line magic

%%claude - cell magic for multi-line prompts

%claude_auth - authenticate (first time)

%claude_reset - fresh conversation

%claude_status - show session info

%claude_version - show version and build SHA

The syntax was inspired by a Databricks talk at a cybersecurity meetup in San Francisco — they use %sql to fire Spark queries inline in notebooks, one magic command and the entire cluster’s compute is yours. Same idea, different familiar.

%claude_version shows the build SHA. %claude_status confirms auth and session state before the first cell runs.

Three ways to talk. ask("prompt") is a plain function — the safest option, handles question marks and special characters without issues. %claude prompt is a line magic — clean syntax, one line. %%claude is a cell magic — write a multi-line prompt in the cell body, good for complex questions with code context.

The Question Mark War

This was supposed to be simple. It wasn’t.

%claude What are the three laws of robotics? → Object 'robotics' not found.

IPython intercepts any trailing ? as an introspection command. Before the magic even sees the input, HelpEnd has already consumed the ? and converted it into an object inspection call. Two approaches — monkey-patching HelpEnd and registering a TokenTransformBase subclass — either failed silently or crashed the kernel. The third worked: register a plain function at position zero in input_transformers_cleanup that strips trailing ? from %claude lines before HelpEnd gets a chance.

The ask() function remains the recommended path — it bypasses IPython’s input transformation entirely since it’s a regular Python function call, not magic syntax.

Streaming: Thinking Aloud

The first version was buffered. The CLI ran in print mode (-p), collected the full response, then rendered it. You’d stare at a blank cell for thirty seconds wondering if anything was happening. The fix was obvious: stream it.

Claude Code has --output-format stream-json — a JSONL stream of high-level CLI events. The format is not the raw Anthropic API delta stream; it’s a higher-level wrapper. Each line is an event with type: "assistant" (containing a complete content block) or type: "result" (final summary). The content blocks arrive whole — thinking first, then text — not token-by-token.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

proc = subprocess.Popen(cmd, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE)

for raw_line in proc.stdout:

line = raw_line.decode("utf-8", errors="replace").strip()

obj = json.loads(line)

if obj.get("type") == "assistant":

for block in obj.get("message", {}).get("content", []):

if block.get("type") == "thinking":

thinking_text = block["thinking"]

elif block.get("type") == "text":

answer_text = block["text"]

handle.update(HTML(_render_streaming(thinking_text, answer_text)))

The thinking section renders as a collapsible <details> block — open while Claude is reasoning, collapsed once the answer arrives. Toggle %claude_thinking to show or hide the reasoning entirely. The final render replaces the streaming HTML: thinking goes into a collapsed <details> with styled borders, the answer renders as proper IPython Markdown.

The Session Resume Bug

The first working build had a subtle defect. Cell 1 succeeded. Cell 2 failed:

1

Error (exit 1): Session ID 6b1651a7-... is already in use.

--session-id creates a new session. It doesn’t resume one. For subsequent turns in the same conversation, the flag is --resume. A boolean _session_created flag (separate from the turn counter) tracks the boundary — if the first turn exits cleanly but produces no output, the turn counter stays at zero but the session still exists. Using _turn_count == 0 as the guard would recreate it on the next call and fail again.

1

2

3

4

5

if not _session_created:

session_args = ["--session-id", CLAUDE_SESSION_ID]

_session_created = True

else:

session_args = ["--resume", CLAUDE_SESSION_ID]

After the fix, conversation memory works across cells. Ask Claude to name three fictional spaceships in Cell 1, ask which it ranked highest in Cell 2, ask it to describe that ship like a used car salesman in Cell 3. Each cell builds on the last. The familiar remembers.

Three cells, one conversation. The context carries forward across each

Three cells, one conversation. The context carries forward across each ask() call.

Auth Persistence

The deployment mounts a 20GB PVC at /home/jovyan/work. The environment variable CLAUDE_CONFIG_DIR points to /home/jovyan/work/.claude — a directory on the persistent volume. OAuth credentials, session history, and project configuration all land on DRBD-replicated storage.

Scale the deployment to zero. Scale it back to one. Different pod, different node, same PVC. The familiar returns already authenticated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

env:

- name: CLAUDE_CONFIG_DIR

value: /home/jovyan/work/.claude

volumeMounts:

- name: data

mountPath: /home/jovyan/work

The only thing that resets on pod restart is the kernel session ID — a new UUID, a fresh conversation. Auth stays. Notebooks stay. The familiar forgets the conversation but knows who you are.

bypassPermissions is wired in at the chart level — a postStart hook writes it to CLAUDE_CONFIG_DIR on first boot. No permission dialogs.

Docker Inside Jupyter

The question kept surfacing: can I build containers from the notebook? Not just write code — build it, package it, test it, push it to a registry. A full development lifecycle without leaving the browser.

Docker-in-Docker is a solved problem on bare metal. Docker-in-Kubernetes is a nightmare. The container runtime runs as an unprivileged user inside a pod, inside a namespace, inside a cgroup — three layers of isolation actively preventing the one thing you need: making more containers.

Podman solves the daemon problem (rootless, daemonless). But rootless Podman in Kubernetes trips over three walls:

- User namespaces:

newuidmapwrites to/proc/self/uid_map. RequiresCAP_SYS_ADMIN. - Overlay mounts: The overlay storage driver needs to remount

/. Denied without full mount propagation. - Root filesystem: Even with

SYS_ADMIN, the container’s rootfs isrprivate. Image layer extraction needsrshared.

Three walls. One sledgehammer: privileged: true.

1

2

containerSecurityContext:

privileged: true

The Helm chart exposes this as an opt-in value. Don’t set it, don’t get Podman. Set it, get a full container runtime. The tradeoff is explicit: the pod escapes its sandbox. For a dev instance behind OAuth2 Proxy, this is fine. For production, use KubeVirt.

With privileged: true, the overlay storage driver works via fuse-overlayfs — the binary was always in the image, waiting for /dev/fuse to be available. The Helm chart exposes a podman.fuseOverlayfs flag: when enabled, it mounts /dev/fuse from the host as a character device and adds SYS_ADMIN to the container’s capabilities. An init script detects /dev/fuse on first terminal open and writes the appropriate storage config — overlay with fuse-overlayfs as the mount program, or vfs as a fallback if the device isn’t there.

The difference matters. vfs copies every layer fully on every pull — a 2.5GB image becomes 17GB of disk IO because there’s no deduplication. overlay snapshots each layer. Same image, fraction of the work. The .bashrc aliases docker to podman for muscle memory. Pull an image, run a container, build a Dockerfile, push to a registry — all from a JupyterLab terminal tab.

1

2

(base) jovyan@jupyter-dev:~$ docker run --rm alpine echo "hello from inside k8s"

hello from inside k8s

Routing Traffic

The cluster already runs a Mullvad VPN proxy pool — six gluetun instances spread across two nodes, each with a different WireGuard keypair and Mullvad exit. The CCTV scraper and ADS-B aggregator use it to avoid IP bans on the data sources they poll. JupyterLab now taps the same pool.

The design is deliberately selective. A full VPN killswitch — iptables routing all pod traffic through WireGuard, the pattern the blockchain nodes use for Tor — would break kubectl, Helm, the Forgejo in-cluster URL rewrite, everything. What’s useful is explicit per-request routing: send this curl through Mullvad, send that curl through Tor, compare results.

1

2

3

4

5

6

%proxy # show usage

%proxy mullvad # random endpoint from the pool

%proxy mullvad 2 # specific endpoint for comparison

%proxy tor # Tor SOCKS5 sidecar

%proxy off # back to node IP

%proxy status # show current proxy + exit IP

Shell equivalents — proxy-mullvad, proxy-tor, proxy-off, proxy-status — are sourced in .bashrc for the same workflow in a terminal tab.

Tor runs as an optional sidecar: tor.enabled=true in Helm values adds a tor-gateway container sharing the pod’s network namespace. No iptables killswitch — the SOCKS5 proxy sits at 127.0.0.1:9050 and you route to it explicitly. The Mullvad side needs no new infrastructure at all: mullvad.proxySecretName points at an existing cluster secret, and PROXY_URLS arrives as an environment variable. The magic reads it at call time.

The original use case: reproducing rate-limit behavior that only manifests under specific exit IPs, without SSH tunneling out of the cluster to a separate machine.

The Loop

The public image has no credentials — it knows nothing about this cluster’s git server, registry tokens, or SSH keys. Credentials arrive at pod startup via Kubernetes Secrets and postStart hooks: gitconfig and SSH key for Forgejo, registry auth for GHCR. The gitconfig includes a URL rewrite so cloning by the external Forgejo URL silently routes through the internal service.

Clone, edit, push, build, deploy. Browser only.

The Dev Instance

The dev instance runs at jupyter-dev.kub0.xyz on the :dev tag. Both releases — production and dev — live in the same jupyter namespace, sharing pull secrets and storage class defaults. Separate PVCs, separate ingresses, same namespace. The production instance at jupyter.kub0.xyz stays on :latest, untouched until the dev image is validated.

The dev image adds tmux (terminal sessions survive browser disconnects), kubectl + helm (cluster operations from inside the cluster), and the full Podman setup for container builds. Same Helm chart, separate PVC, separate ingress, same namespace as production.

What Now Exists

The cluster has a voice.

Open jupyter.kub0.xyz. The OAuth gate checks your GitHub identity. JupyterLab loads with Claude magic pre-registered. Open a notebook. The banner prints the image tag, git SHA, and session ID — you know exactly which build you’re running before you type a single character. Type ask("What's running in the observability namespace?") and watch Claude’s thinking stream into a collapsible block while the answer builds token by token below it. Ask a follow-up in the next cell. The conversation carries forward.

Open a terminal tab. Run docker pull ghcr.io/kub0-ai/jupyterlab-claude:dev. You are now pulling the image of the container you’re sitting inside from inside that container. Build a new version, push it to the registry, and the next pod restart picks it up. It’s containers all the way down.

It’s not an assistant sidebar. It’s not a chat window bolted onto an IDE. It’s a computational environment where natural language, Python, and container runtimes share the same execution context. The notebook cell is the interface. The terminal is the workshop. The kernel is the session boundary. The PVC is the memory.

Claude runs with bypassPermissions enabled — it can execute commands, read files, write code, and push changes without stopping to ask. That’s the autonomous mode. What’s missing is the notification layer: when Claude is running unattended and hits something that needs a human decision, something has to wake you up. Hooks are the next ligament.

The chart and image are public at kub0-ai/jupyterlab-claude. v0.1.0 is tagged on GitHub. Anyone can install it, point it at their own git server, bring their own registry credentials, and get the same familiar in their own cluster. The binding pattern isn’t specific to this stack — it’s just Claude Code CLI, IPython, and a UUID.

Going public has a short grace period for mistakes. Within hours of tagging v0.1.0 and pushing to GitHub, the initial commit surfaced in the history — chart/Chart.yaml had been authored with the internal Forgejo URL as the chart’s home and sources fields. A later commit had corrected it. The file was clean. The history wasn’t.

The fix was blunt. The repo was six hours old, fifteen commits deep, sole developer. git checkout --orphan clean-main, stage everything, single commit, delete the old branch, force-push to both remotes. v0.1.0 tag recreated on the new commit. History gone — because there was no history worth keeping.

The defense is a pre-push hook that runs before anything leaves the machine. It scans every commit in the push diff for patterns: internal domains, Tailscale IP ranges, vault path fragments. Catches it before it becomes a six-hour incident. The template propagates automatically to new repos via git config --global init.templateDir.

Squashing for history-scrubbing is unusual — normally you’d use git filter-repo to rewrite specific strings across an intact history. But for a fresh solo project, a clean single commit is equivalent to “here’s the current state.” Commit history is for collaboration and archaeology. Neither applies yet.

After that: local inference. An Ollama deployment on aus-fwd-gpu-02 — the same Austin node the Forgejo Actions runner now lives on, with 96GB of GPU RAM already carved out in BIOS. Not waiting for a job — waiting for a model. The training starts now.