The Overwatch Map: When Cameras and Aircraft Share a Canvas

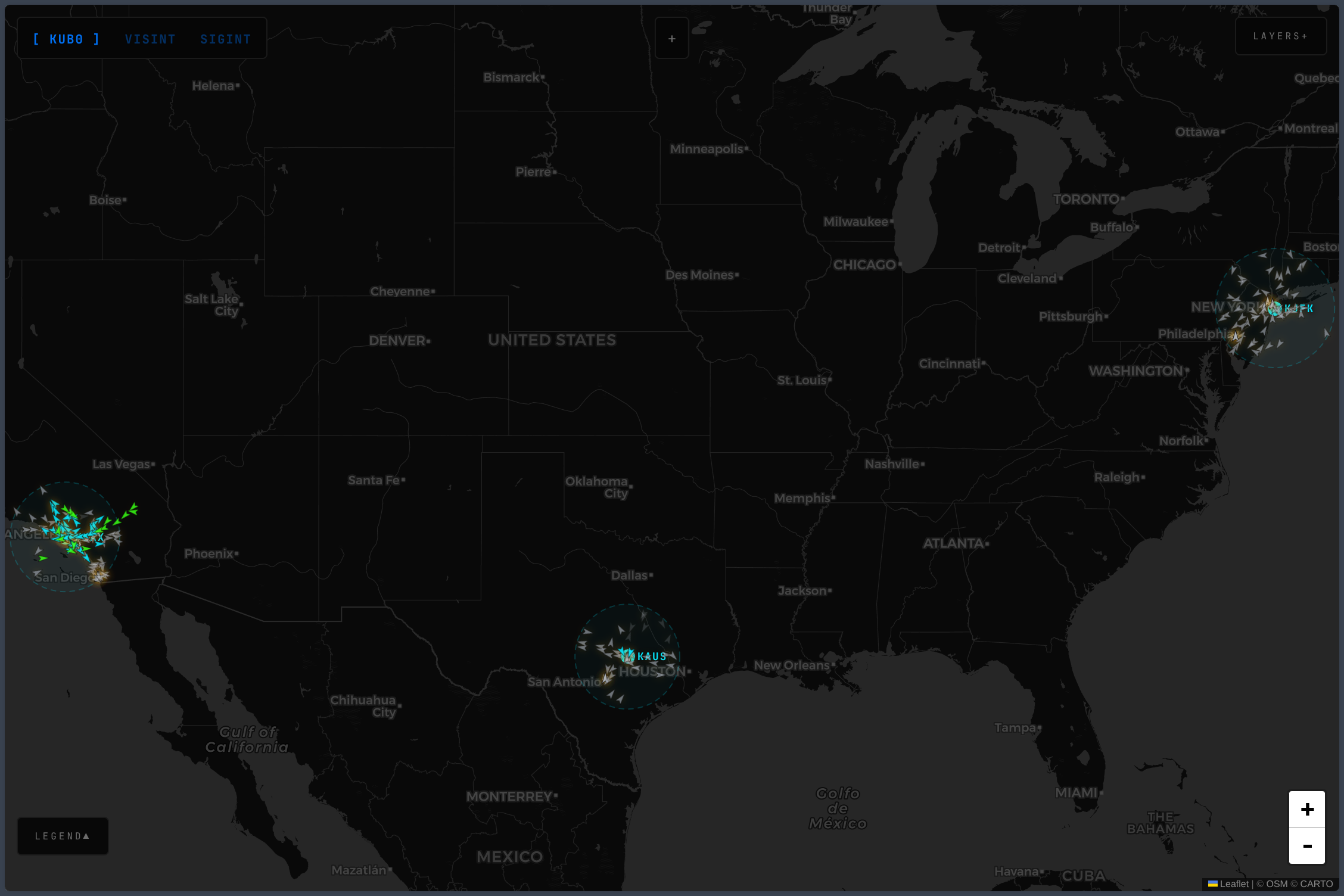

6,081 cameras across three countries on a dark map. SVG plane icons rotating by heading, refreshing every five seconds. Coverage rings over Austin, LA, and Tokyo — three SDR receivers, three windows into the sky.

The All-Seeing Eye built the camera scraper. Every Thirty Seconds gave it ears. One update since: the scraper now crops top and bottom of each frame before hashing — timestamp overlays were triggering false “changed” detections on otherwise static cameras. Everything else runs as documented there.

Overwatch

intel.kub0.ai is a full-viewport Leaflet map on dark CartoDB tiles. Two data layers, two refresh cycles, one canvas.

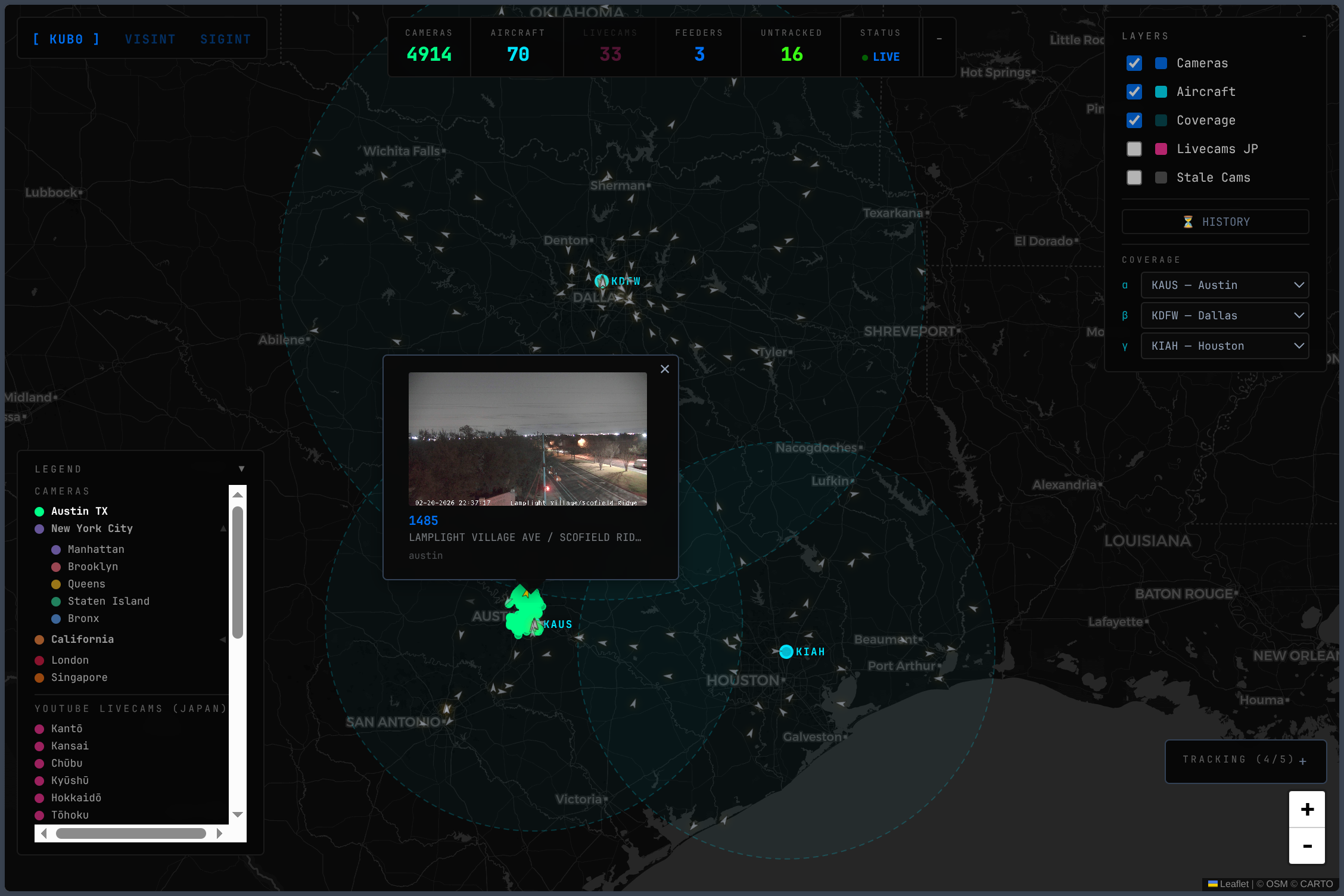

Cameras refresh every five minutes — ~6,100 circleMarkers rendered via preferCanvas: true. District coloring is handled in the CCTV API. Stale cameras fade to grey. Click a district in the collapsible legend to zoom and filter.

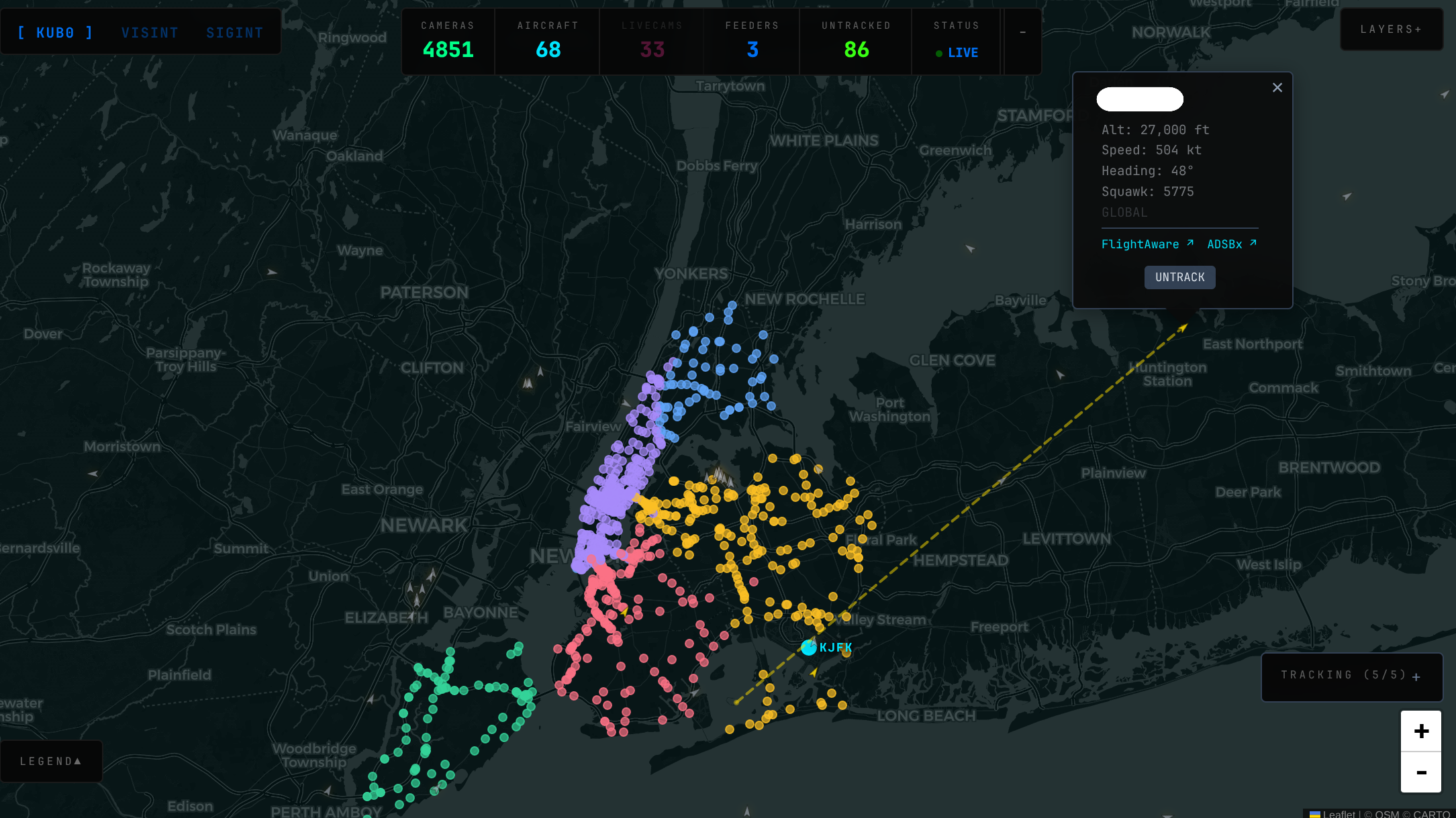

Aircraft refresh every five seconds: SVG plane icons rotated by track heading, colored cyan. Each feeder — Austin, LA, Tokyo — contributes its visible aircraft, deduplicated by hex transponder code. Select up to three airports for ADS-B coverage rings at ~150 nautical miles each.

Twenty-nine Japan livecam markers (pink) overlay the map alongside traffic cameras: train platforms, harbor approaches, volcanic peaks. Click one for a live YouTube embed. Resolution and embed mechanics are in The All-Seeing Eye.

The Proxy Pool

One IP hitting 3,370 CalTrans cameras every twelve minutes doesn’t go unnoticed forever. No phone call. No email. Just 403s, then timeouts, then 429s.

Six Mullvad/gluetun WireGuard exits across two hosts. Docker Compose, not Kubernetes — gluetun captures all container traffic via iptables, which would break CoreDNS, liveness probes, and pod networking inside a cluster. Docker Compose keeps the blast radius contained.

Two traps during setup. gluetun’s proxy port returns Unsupported scheme when hit directly — it expects proxied requests. The actual health server runs on port 9999, undocumented until you read source or fail ten times. Mullvad’s WireGuard registration returns 10.x.x.x/32,fc00:xxxx:xx01::x:xxxx/128 — IPv4 and IPv6, comma-separated. gluetun only supports IPv4; strip everything after the comma before passing the address.

On the cluster side, an atomic round-robin pool distributes requests without locks. PROXY_URLS is optional — empty means http.DefaultTransport, direct connections. The proxy is an overlay, not a dependency. The 429s stopped.

The Flights API: Filling the Gaps

Each feeder covers ~150 nautical miles. Austin and LA overlap in West Texas. Tokyo covers Kanto. The Pacific, the Midwest, Southeast Asia — void.

A standalone Go service runs two loops. The fast loop polls all three feeders every five seconds. The slow loop queries airplanes.live every thirty seconds. Feeder aircraft always win on merge (freshest data); airplanes.live fills the gaps with _source: "global". The frontend makes one fetch instead of three.

At peak, airplanes.live returns 8,000 aircraft — which renders as a slideshow, not a map. The public frontend filters global aircraft entirely; only feeder-sourced planes appear. Global data feeds the internal flights.kub0.xyz dashboard.

The real insight the map is being built toward: visual distinction between enriched aircraft (feeder-sourced, matched to a registration and operator in the database) and dark aircraft (feeder-sourced, broadcasting ADS-B but invisible to every public tracking database — LADD opt-outs, military, private). Right now they all render cyan. The signal is there; the map just doesn’t surface it yet.

On-demand enrichment hits hexdb.io on click — free, unauthenticated, 429s happen regularly. The LA feeder catches enough traffic that the coverage is genuinely useful. Austin and Tokyo get there. Enrichment itself is still best-effort and the visual language to act on it is still in progress.

Tokyo Goes Dark

After eleven hours, the Tokyo coverage ring showed exactly zero aircraft. dump1090 was decoding 254,000 messages.

Two bugs compounded. The Kubernetes secret wiring the proxy pool to the service didn’t exist — optional: true means Kubernetes silently skips missing secrets, the env var reads as empty, the pool initializes nil. Six weeks of correct proxy code sat inert. Second: deterministic round-robin meant Tokyo queries always hit the same two Frankfurt exits, getting both blocked after eleven hours of thirty-second hammering from a Japanese ISP address.

Both fixes together — create the secret, replace round-robin with rand.IntN(len(p.proxies)), add 429-aware retries with 10/20/30s progressive delays — cleared the block. Two retries, 51 aircraft over Japan.

A commit is not a deployment.

Click to Track

A thousand aircraft on a map is information. One aircraft on a map is intelligence.

Clicking opens a popup — callsign, altitude, speed, heading, enrichment. Tracking goes further: POST /track/{hex} adds the aircraft to a dedicated 10-second polling loop at api.airplanes.live/v2/hex/{hex}, independent of global queries. The tracked aircraft turns golden, the map follows it, a dashed polyline traces its path. Up to five concurrent tracks (server-enforced via MAX_TRACKED). The HUD shows TRACKING (2/5) with the focused aircraft marked ▸ and others dimmed. Each has an × to untrack individually.

The public map stores tracked aircraft in localStorage — every visitor’s set is their own, invisible to other sessions. The internal flights.kub0.xyz dashboard uses shared server state intentionally. Two frontends, two isolation models, same backend.

Aircraft popups carry links to FlightAware for flight history and ADSBexchange for global hex tracking. The intel map tells you what’s overhead now. The links tell you where it came from and where it’s going.

Some aircraft on the map carry no enrichment data — no registration, no operator, no type. They’re broadcasting ADS-B (your hardware hears them) but they’ve opted out of public tracking databases via the FAA’s LADD program. Commercial platforms won’t show them. The raw feed does. You can click them, get a hex code, track them across the sky. But on the map they look identical to a fully identified United 737. That’s the gap — the data to distinguish them exists, the visual language to act on it doesn’t yet.

Squawk 7700

| Code | Meaning | What It Signals |

|---|---|---|

| 7500 | HIJACK | Unlawful interference with the aircraft |

| 7600 | NORDO | Radio failure — no communication capability |

| 7700 | EMERGENCY | General emergency — could be anything |

The backend scans every aircraft on each metrics tick. A match triggers a dark red panel with pulsing border — the code, its meaning, the callsign. Emergency aircraft render at z-index 3000, above everything else. Click the alert and the map auto-tracks that aircraft.

Real 7700s are rare — most pilots go entire careers without squawking one. The panel exists for the same reason smoke detectors exist.

Going Global

Four thousand cameras, all in the United States. Two public APIs changed that.

Transport for London JamCams — no registration, no key, no visible rate limits. One request, 884 cameras. Two bugs on first contact: the documentation describes a nested location sub-object; the actual API returns lat and lon at the top level. The url field is a relative path; the real image URL is in additionalProperties under key: "imageUrl". Ten minutes to fix, 884 cameras.

Singapore LTA DataMall requires a registration form. Credentials arrived within the hour. Both immediately returned 404 Not Found. Every third-party tutorial cites Traffic-Images. The actual API User Guide v6.7, page 36, says Traffic-Imagesv2. The v2 endpoint has existed since at least 2020. The PDF is the only place with the right answer. 90 cameras on five-minute rotating S3 URLs.

A collapsible legend tamed the growing region list. The map currently covers 3 countries and ~6,100 cameras — California, Texas, New York, London, Singapore.

~6,100 cameras, three continents of transponders, twenty-nine Japan livecams streaming from train platforms and a volcanic crater. The Overwatch map draws all of it on one dark canvas — or tries to. The rendering holds, the data flows, the enrichment is spotty. The distinction between a known aircraft and a dark one doesn’t show on screen yet.

That’s the map as it exists. The map as it should exist is still being built.

First though, it needed to learn who to trust.